2025 Broadband Advocacy Targets / Target 1

2025 Broadband Advocacy Target 1

MAKE BROADBAND POLICY UNIVERSAL

By 2025, all countries should have a funded National Broadband Plan (NBP) or strategy, or include broadband in their Universal Access and Service (UAS) Definition

Action to enhance broadband access is more likely when there is a national broadband plan or strategy in place, and/or when broadband is included in countries’ Universal Access/Service (UAS) definitions.

The Broadband Commission has been tracking National Broadband Plans (NBPs) and strategies adopted by countries globally for over 10 years, and originally named “Universal Broadband Policy” the first of its four main targets which were established in 2011. The target was revised in 2016 with an increased emphasis on implementation capacity through the specification of how plans and strategies are funded. Progress on this target is tracked annually in our flagship State of Broadband report. Since the first edition of the report, there has been a notable increase in the number of countries with NBPs or strategies, but more work must be done to monitor and evaluate the current state of implementation of these national plans.

Tracking progress

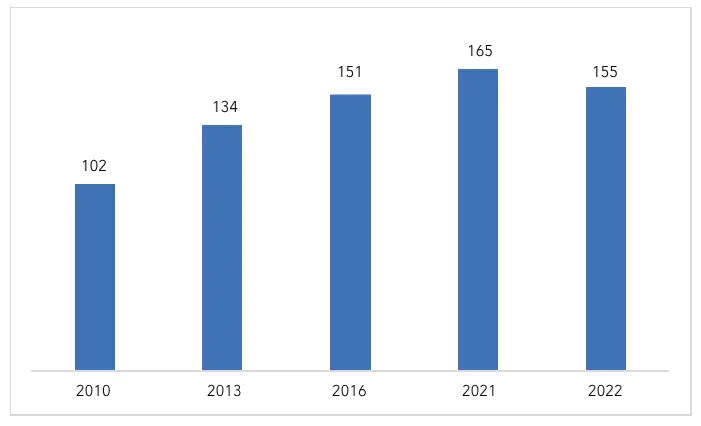

155 countries had a national broadband plan or other digital strategic document emphasizing broadband in 2022, down from 165 in 2021. The number of economies with a broadband plan has slightly decreased over the past year, as several plans have expired and have not been renewed in some countries. One positive note is that the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) and the Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report has been working with countries towards the development of a benchmark on digital transformation as part of the follow-up to the 2022 Transforming Education Summit, following a decision of the SDG 4 High-level Steering Committee. While no indicator can cover all three aspects of digital transformation comprehensively (i.e. content, capacity, and connectivity), school internet connectivity is already a Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 indicator (4.a.1), and is therefore being monitored by countries and reported at the international level. Countries have ben therefore asked to share by September 2023 their school connectivity national targets for 2025 and 2030. In the coming years, improvements can be made in how the indicator is sourced, such as adding information from internet service providers.

Transformative risks and opportunities

Monitoring and evaluation needed

More work needs to be done to monitor and evaluate the current state of implementation of these national plans. While plans may have been announced, operationalization and implementation are key to providing actual access to broadband. In addition, as mentioned above, some plans have expired and have not been renewed in some countries. This decrease is linked to changes and evolution in the sector with several countries integrating broadband development plans within broader digital agendas, strategies, and/or masterplans. For example, Canada integrated its broadband plan within the High-Speed Access for All: Canada’s Connectivity Strategy 2022.

In addition, there was a change in policy focus, as noted in the ITU’s Global Digital Regulatory Outlook 2023. The 2008 global financial crisis crowded out private investment in the short term but propelled broadband connectivity to the top of government agendas in all regions, unlocking both unprecedented state investment and market incentives for telecom players. Since then policy levers have targeted infrastructure challenges from investment to digital inclusion to innovation. Gradually, the link between development goals and telecom policies has matured, recognizing the contribution of digital technologies to national economies (see figure below). Universal access and service policies – the bedrock of telecom reform – have been transformed into cross-sector infrastructure policy with an increasing number of countries now adopting a national broadband strategy.

The global pandemic has triggered market disruption as well as unprecedented policy responses, with native digital agendas leading the way to economic recovery. This new generation of policy narratives has reframed the surge of technologies and business models in the new normal, matching markets with future-facing legal frameworks, and shifting focus back to people and long-term development. Native digital agendas, such as the European Commission Digital Compass (implemented through the Digital Decade Policy Programme) and Malaysia Digital Economy Blueprints, cover multiple economic sectors, setting holistic development and economic goals and identifying fast-track implementation mechanisms.

Re-examining the gaps, understanding their nuances

When considering the goal of achieving “universal broadband access,” it is essential to review various gaps in access. As observed earlier, relying solely on the presence of the USAF is insufficient to assess the achievement of universal broadband access, even though it represents a step in the right direction. In the next stage of developing broadband accessibility, there is a need to check where access gaps persist, the nature of these gaps, and breaking down the USAF to parts to understand and update concepts such as what constitutes “sufficient” broadband – for what kinds of activities e.g. education, business, socialising etc? Where is the demand coming from, what will be driving the request for connectivity? And are there assessments of the quality of broadband being delivered, including sustained access? While these nuances will overlap with other Advocacy Targets, a holistic view of these nuances will be critical in seeking to close these gaps.

Understanding mobile broadband coverage and usage gaps within a country can support with the creation of national broadband plans and with the effective utilisation of existing USAFs. The coverage gap, the percentage of people not yet covered by mobile broadband, can help countries determine where to focus efforts on mobile infrastructure expansion. Addressing the usage gap is a much larger challenge. The usage gap is the percentage of people living within the footprint of a mobile network but not yet using mobile internet. Research conducted by the GSMA has found that people face five main barriers to mobile internet adoption: access, affordability, knowledge and digital skills, relevance, and safety and security. By understanding the size and nuances of the usage gap, countries can make policy decisions to address these five barriers.

No one-size-fits-all technology solution

In addition, the technology funded by USAFs should depend on the specific area and complementary connectivity solutions, and should not be a single, one-size-fits-every person, area, and situation. A mix of different technologies e.g. fibre, terrestrial wireless and satellite technologies – should be available for funds as is most appropriate. Recent entry into service of Very-High-Throughput Satellites in the Geostationary Orbit, rapid advances in development of satellite constellations in the Low-Earth Orbit as well as several business partnerships between satellite and terrestrial telecommunications actors (e.g. advanced efforts to provide in the future ubiquitous and cost-effective direct satellite-to-mobile capabilities) point to the existence of numerous possibilities for service providers to extend their networks to achieve unlimited global coverage. The criteria for allocation of funds could consider a combination of technology-neutral approaches, consultations with industry etc.

Rethinking funding programmes

Around 100 countries call on the use of universal service and access funds (USAFs) to deploy infrastructure in unserved areas. However, not all funds have been successful in extending coverage for a variety of reasons e.g. by policy design, mismatch in funding and disbursements etc. For example, an ITU report on financing universal access in 2021 highlights the need for a change in thinking including alternative funding models as a way forward to “Universal Service and Access Fund 2.0”.

The scope of such funding could also extend beyond infrastructure to digital transformation (such as in the scope of the European Union’s Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) for digital)including targeting underserved groups such as women and girls, people with disabilities and the elderly regardless of where they live, as well as the micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs). Other considerations could include alignment of incentives with implementation partners and long-term bankability / financial sustainability of the project. Reforms to existing USAFs should also be informed by internationally recognized best practice, such as the recommendations developed by the Broadband Commission’s Working Group for 21st Century Financing Models. Among others, measures can include broadening the base of contributors to USAFs and other mechanisms by including companies participating in and benefitting from the digital economy.

For over a decade, the Broadband Commission has tasked its multi-stakeholder membership to develop policy recommendations that are critical to realizing universal connectivity. These recommendations are published annually in the Commission’s Flagship State of Broadband Reports. For reference, we have consolidated 10+ years of reports to present the Commission’s key steps for the Decade of Action to ensure global implementation and adoption of broadband and achieve the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals.